The violence consuming eastern Congo shows the bloody cost of energy transition

BLAISE NDALA

SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL, CANADA

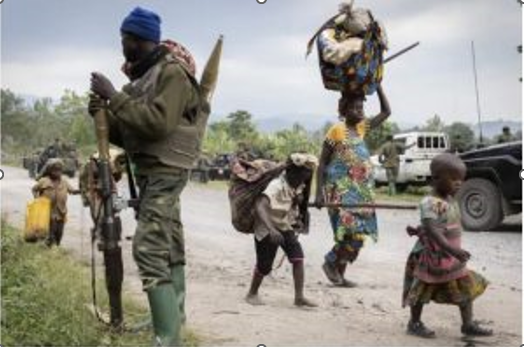

People walk on the Rutshuru-Bunagana road during clashes in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, on Aug. 16, 2022.

People walk on the Rutshuru-Bunagana road during clashes in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, on Aug. 16, 2022.

“Blaise Ndala is the author of the new novel, In the Belly of the Congo. This essay by Blaise Ndala was translated from the original French language version by Pablo Strauss.”

One day in August, 1908, not long before the colony known as the “Congo Free State” was ceded to Belgium, a young aide-de-camp of King Leopold II named Gustave Stinglhamber made his way toward the wing in the Palace of Laeken where a friend of his worked. Nearly a quarter-century earlier, the Berlin Conference of 1884-85 had granted the Belgian monarch control, in a personal capacity, of a newly formed colony 80 times the size of Belgium. As the two friends approached a window, Stinglhamber sat down on a radiator – only to leap back up. It was boiling hot. A custodian was summoned to explain.

“My apologies. We are burning the state archives.”

Author Adam Hochschild reports that it took eight straight days to reduce the archives of the Congo Free State to ashes.

“I will give them ‘my’ Congo,” the King told Stinglhamber, “but they have no right to know what I did there.”

Some hundred years later, in May, 2008, the multinationals Barrick Gold Corp. and Banro Corp. filed a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP) against the small Montreal publisher Écosociété and the three authors of a French-language non-fiction book, Noir Canada: pillage, corruption et criminalité en Afrique (Black Canada: Plunder, Corruption and Criminality in Africa). The book challenged Canada’s image as a “friend of Africa” and examined Canada’s role in deadly African conflicts. Barrick and Banro sought combined damages of $11-million. It was David against Goliath, and Goliath won: Noir Canada was pulled from bookstores and Canadians were kept in the dark about what the mining companies may or may not have done.

At first glance, the palace meeting in early 20th-century Belgium seems unrelated to the lawsuit against the Canadian publisher. Nothing could be further from the truth. Though separated by a century, both events elucidate the violence playing out today in the eastern part of the nation ruled as the personal fiefdom of King Leopold II, and then as a Belgian colony until independence in 1960.

Over the past 29 years, the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo has been a theatre of violent conflict. The area’s vast mineral wealth is the cause of cyclical wars that constitute a simple yet crushingly effective strategy: sow terror to undermine the state that sits on one of the world’s richest stores of minerals, place mining regions under military occupation, and co-ordinate the plunder – all under the gaze of curiously powerless UN peacekeepers.

Blood in our phones

In the late 19th century, the Congolese people were brutally exploited in service of the burgeoning auto industry, as Western interests scrambled to extract the rubber from tropical forests needed to make tires. Leopold II’s men forced local populations to harvest resources through torture that included cutting off the hands of Congolese who failed to meet their quotas, an atrocity brought to light by the English missionary and photographer Alice Seeley Harris.

In the 21st century, multinational corporations are exploiting the same region, driven by the imperatives of the transition to “clean energy.” Eastern Congo teems with the minerals needed for this crucial shift: the cobalt, coltan, lithium, tin, tantalite and others found in our smartphones and laptops – as well as wind-turbine generators and electric-vehicle batteries.

Experts forecast surging global demand for these metals and minerals in the years ahead. But already, the market for these resources has spawned international organized criminal networks working hand in hand with local militias and the Rwandan and Ugandan armies, whose direct involvement in the conflict in eastern DRC has been thoroughly documented by NGOs and the UN. The repeated UN Charter violations culminated in the June, 2000, war between Rwandan and Ugandan forces in Kisangani, the DRC’s third largest city, over control of the area’s diamond mines.

M23 soldiers leave leave Rumangabo camp after a meeting between EACRF officials and M23 rebels on Jan. 6.

M23 soldiers leave leave Rumangabo camp after a meeting between EACRF officials and M23 rebels on Jan. 6.

And while predatory forces feast on the nation’s mineral wealth, Congolese civilians pay the heavy price of these hostilities, or find themselves forced into exile. The capture of Rutshuru and Kiwanja in October, 2022, by M23 rebels, backed by the Rwanda Defense Force, and continuing violent clashes near Goma are merely two of the most horrific examples.

Rape as a weapon of war

Between 1885 and 1908, outrage over the crimes orchestrated by Leopold II, champion of “free trade,” sparked the first international campaign for humanitarian law. International figures such as Mark Twain and Edmund Dene Morel, co-founder of the Congo Reform Association, led the denunciation of the mass slaughter for “red rubber.” When the horrors photographed by Alice Seeley Harris attracted international notice, the Belgian monarch was forced to cede “his” Congo to Belgium, a royal gift accepted on the condition that it turn a profit.

In 2022, as the FIFA World Cup stirred up controversy and boycott threats over the choice of Qatar as host nation, Paul Kagame’s Rwanda was calmly gearing up to hold the first Road World Championships of cycling on African soil, with boasts of its picturesque charms and “healthy business climate.” Capitalizing on Western guilt over the failure to prevent the 1994 Rwandan genocide of Tutsis, Mr. Kagame is now pursuing his sinister agenda in the Congo secure in the knowledge that neither the African Union nor any of the voices so quick to cry foul at “rogue states” such as Iran and China will stand in his way.

Residents flee fighting between M23 rebels and Congolese forces near Kibumba, some 20 kilometres north of Goma. The accounts are haunting and include reports of abductions, torture and rapes.

Residents flee fighting between M23 rebels and Congolese forces near Kibumba, some 20 kilometres north of Goma. The accounts are haunting and include reports of abductions, torture and rapes.

The desperate plight of the Congolese has no more eloquent spokesperson than Denis Mukwege, the physician nicknamed “the man who repairs women” for his work healing women who are victims of sexual violence, and director of the Panzi Hospital and Foundation since 1999. When Dr. Mukwege denounces the use of “rape as a weapon of war” in the Kivu region, he speaks from long experience treating victims. And since winning the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize, Dr. Mukwege has used his international platform to repeatedly demand the one thing that could truly make a difference for the many women who use his hospital and for the DRC generally: an end to impunity. Dr. Mukwege calls for a special criminal tribunal for the DRC like those formed in the wake of other conflicts, from neighbouring Rwanda to the former Yugoslavia. These tribunals have helped victims of trauma work toward healing, and states scarred by intractable armed conflicts regain a semblance of cohesion.

Burying the evidence

Two items in Dr. Mukwege’s arsenal should, in theory, leave the international community without plausible deniability: the 1993 UN Panel of Experts report on the plunder of natural resources in the DRC, and the 2003 UNHRC report, Mapping Human Rights Violations in the DRC (1993 to 2003). By identifying the presumed perpetrators of a tragedy with far-reaching ramifications, these reports held out hope to the Congolese people that the crimes committed against them might not be allowed to continue unpunished. Yet as I write, Congolese blood is still flowing in Kivu, while the reports sit in drawers at the UN Security Council. Under pressure from the Rwandan President and his Western sponsors to make them disappear, will these reports share the same fate as a large part of Leopold II’s archive?

The Congolese people are asking for no more than the enforcement of international law, the same law that has caused the (justified) ostracization of Vladimir Putin’s Russia and a groundswell of support for Ukraine from powers raising the spectre of a breakdown of the world order. The people of the DRC know full well that, with or without foreign allies, they will have to fight to preserve the right to enjoy their own land. They also know that they cannot willfully ignore the inner demons that are corroding from within a country of measureless potential.

And then there is us.

The assets of Canadians, through the Toronto Stock Exchange, pension funds, RRSPs, public investments and other instruments, fund many of the companies singled out for wrongdoing in the UN reports on crimes in the DRC. Although the Canadian government has remained silent since the war in Kivu resumed, it is our duty as citizens to not turn a blind eye to the suffering in the Congo.

Upholding this duty means asking tough questions. What can we do, as consumers and as voters, to break the silence surrounding crimes whose death toll since 1998 exceeds the population of British Columbia? The perpetrators of these crimes are known. They are individuals, corporations and states that believe themselves untouchable. I, for one, refuse to believe that being collectively complicit in their impunity is the only choice we have.

This article was originally published in the hard copy edition of the Globe and Mail Newspaper (OPINION SECTION) on Saturday: March 11, 2023

Send your comments to feedback@thecanadianvanguard.ca. Readers who want their opinion published should include full verifiable contact details along with their own opinion. The Canadian Vanguard WILL never sell your data. The company will also do the utmost to secure all data including third party data.