Canada gives preference to French-speaking economic immigrants during selection – and bypasses stronger candidates in most cases

The federal government is prioritizing French-speaking economic immigrants, a shift that has often seen higher-ranking applicants bypassed in the selection process, according to a Globe and Mail analysis of figures published by the Immigration Department.

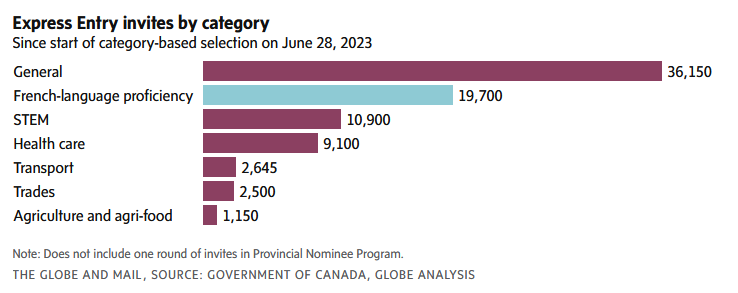

Since it overhauled the Express Entry system for skilled immigration last year, Ottawa has invited 19,700 people to apply for permanent residency based on their French skills, easily more than in other new categories for selection. The government has also extended 36,150 invites to the broad pool of candidates, whose selection is based solely on points rather than specific attributes.

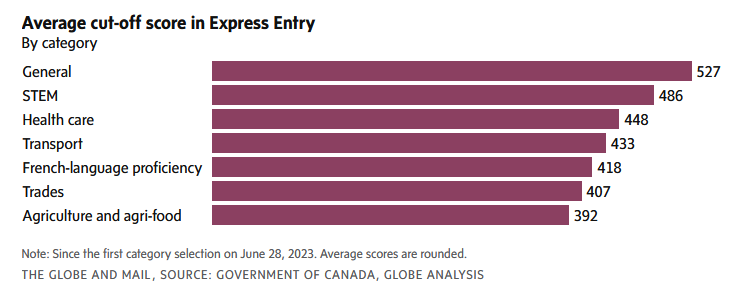

To pick these French speakers, the government is effectively reaching deeper into the pool of immigration candidates, which means the cutoff score for entry is frequently much lower in this category than in others. These individuals have lower expected earnings in Canada than people with higher scores.

“What’s the objective here? If it’s about economic growth, then this is not a smart policy,” said Mikal Skuterud, an economics professor at the University of Waterloo. “But clearly, that’s not what this is about. They’re using economic-class programs to achieve different objectives.”

With last year’s shakeup of Express Entry, the federal government can now invite people to apply for permanent residency based on their work experience in certain occupations within five sectors: health care, skilled trades, agriculture, transportation and STEM (science, technology, engineering and math). It also created a category for French speakers.

Ottawa has said these changes are aimed at alleviating labour shortages and supporting francophone communities outside Quebec. (As part of a 1991 deal with the federal government, Quebec runs its own system for economic immigration.)

Express Entry, which accounts for a large portion of economic immigration to Canada, uses a points system to rank candidates. Each person is assigned a score under the Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS), which takes into account factors such as age, education and competency in English or French. The scores are meant to predict a candidate’s earnings in Canada, based on outcomes for previous immigrants.

Before last year’s changes, the government would regularly invite people with the highest scores to apply for permanent residency. The idea was to select the candidates with the highest earnings potential.

But in filtering for certain attributes, the government is recruiting individuals from a smaller group, which means their scores are lower – along with their expected earnings.

“You’re always going to do worse if you restrict your applicant pool,” Prof. Skuterud said.

For example, on Feb. 29, the government invited 2,500 people from the French-language category to apply. The CRS score of the lowest-ranked invitee was 336. A day earlier, the cutoff score in a general round of invites was 534.

It is difficult to characterize the almost 200-point difference between those individuals, because their scores are based on a variety of factors. However, the French speakers with considerably weaker scores may be older and less educated, have less work experience and weaker language skills, or some combination thereof.

Since the start of category-based selection last year, the average cutoff score in the French category over nine rounds of invites has been 418. The benchmark has been lower in the trades and agriculture categories, from which the government has invited far fewer people to apply for permanent residency.

Some economists have criticized this general approach to immigrant selection – not solely the focus on French speakers – because it means that desirable candidates are being overlooked. Since the first category-based selection in June, 2023, Ottawa has issued nearly 46,000 invites through these new categories, compared with 36,150 to the broad group of candidates.

“It is definitely going to affect our ability to select the top talent,” said Parisa Mahboubi, a senior policy analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute.

The federal government has said it is using the Express Entry system to boost francophone immigration. This year, it is aiming for 6 per cent of total permanent residency admissions to be French speakers outside Quebec. The target will rise to 8 per cent by 2026.

“Supporting Francophone immigration has been, and continues to be, a key Government of Canada priority,” said Julie Lafortune, a spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, in a statement. She noted the government is trying to restore and increase the demographic weight of francophone and Acadian communities.

Ms. Lafortune said the categories aren’t mutually exclusive. If a French-speaking nurse were selected to apply for permanent residency, he or she would count toward the government’s recruitment goals in both areas (French and health care), regardless of which category was used for selection, including general rounds of invites.

Anne Michèle Meggs, a former director of planning and accountability at Quebec’s Immigration Ministry, said it was unlikely Ottawa was selecting French speakers to curry favour with certain communities ahead of the next federal election. “There are not a lot of votes to find among francophones outside Quebec,” she said.

Ms. Mahboubi said she would prefer a system based purely on selecting people with the most points, in line with previous practices. “The goal of Express Entry should be to select the top candidates and the top economic immigrants,” she said.

This article was first reported by The Globe and Mail