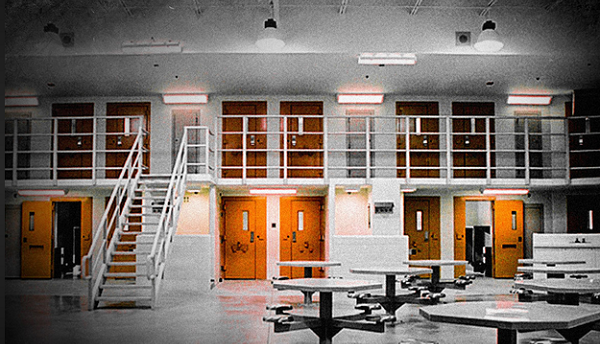

Ottawa considering jailing immigration detainees in its prisons while other provinces turning them away

Human rights advocates have been caught off guard by Ottawa’s plan to use federal prisons to hold immigration detainees now that all provinces have decided to stop housing them in maximum-security provincial jails.

After a successful two-year campaign to get the 10 provincial governments to end the practice, Samer Muscati of Human Rights Watch Canada was disappointed by the federal plan to further invest in the incarceration of migrants for violating immigration laws, even though it referred only to “high-risk” immigration detainees.

Buried in this week’s federal budget, the Trudeau government committed $325 million over five years to upgrade immigration holding centres “to enable secure detainment of high-risk individuals.” It also plans to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and the Immigration Act to enable the use of federal jails as a “supplement.”

“It’s troubling it was announced in this way, with no prior notice that the federal government would be moving in this direction,” said Muscati, whose organization led the #WelcomeToCanada campaign with Amnesty International in 2021 to lobby provinces to stop jailing immigration detainees with the criminal population.

“They’re not only investing more in the federal immigration detention centres, but now they’re looking at amending and codifying into law the use of federal prisons for the purpose of immigration detention.”

Last month, the campaign reached a milestone when Newfoundland and Labrador became the last province to commit to end its immigration detention agreements and arrangements with the Canada Border Services Agency, hoping to push Ottawa to work toward ending the practice of immigration detention altogether.

“As far as the last time we heard from the federal government, it looked like they were taking our recommendations seriously,” Muscati recalled. “We’re certainly caught off guard.”

The CBSA said detention in a provincial facility, where the measure is still available, is limited to the most difficult cases.

“When someone is held for ‘unlikely to appear,’ they may also have prior convictions and outstanding charges for violent crimes,” said a spokesperson for the agency. “They may have demonstrated violent, non-compliant, and unpredictable behaviour that places them, other detainees, the guards and medical personnel at risk.”

As of March 15, there were 12,809 people who have been released and are living across the country with conditions as alternatives to detention; 193 people detained in the agency’s three immigration holding centres; and 49 others remaining in provincial jails or local police holding cells.

Migrants are detained when officials are unsure of their identities or consider them a flight risk or a safety threat to the public or to themselves. But University of Toronto law professor Audrey Macklin said it’s problematic to penalize migrants and place them in detention on those grounds as if they were convicted criminals.

She said research has consistently shown that it is more cost-effective and yields better outcomes to look at alternatives to detention such as release on surety or community-based supervision.

“The point of not using provincial jails to detain people for immigration reasons was not to shift them over to the federal system, but rather to shrink the unnecessary use of immigration detention,” said Macklin, chair in human rights at the U of T law school. “It seems, both financially imprudent and for principled reasons, ill-advised.”

This article was first reported by the Star